Việt Nam and the Asia Pacific Triennial

Articles & Posts (EN)https://apap.qagoma.qld.gov.au/viet-nam-and-the-asia-pacific-triennial

Abigail Bernal

When artists from Việt Nam featured in ‘The First Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art’ (APT1), at the Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia, in 1993, both nations were looking outward — Australia to the Asia Pacific region, and Việt Nam to a capitalist world, following a period symbolised by the collapse of state-controlled, subsidised systems and the adoption of Đổi Mới economic reform policies in 1986.1 Over a period of some 30 years, more than 25 artists from Việt Nam have exhibited in the Triennial, their work offering a snapshot of Vietnamese contemporary art and society, and evolving curatorial and artist relationships.

The First Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT1, 1993)

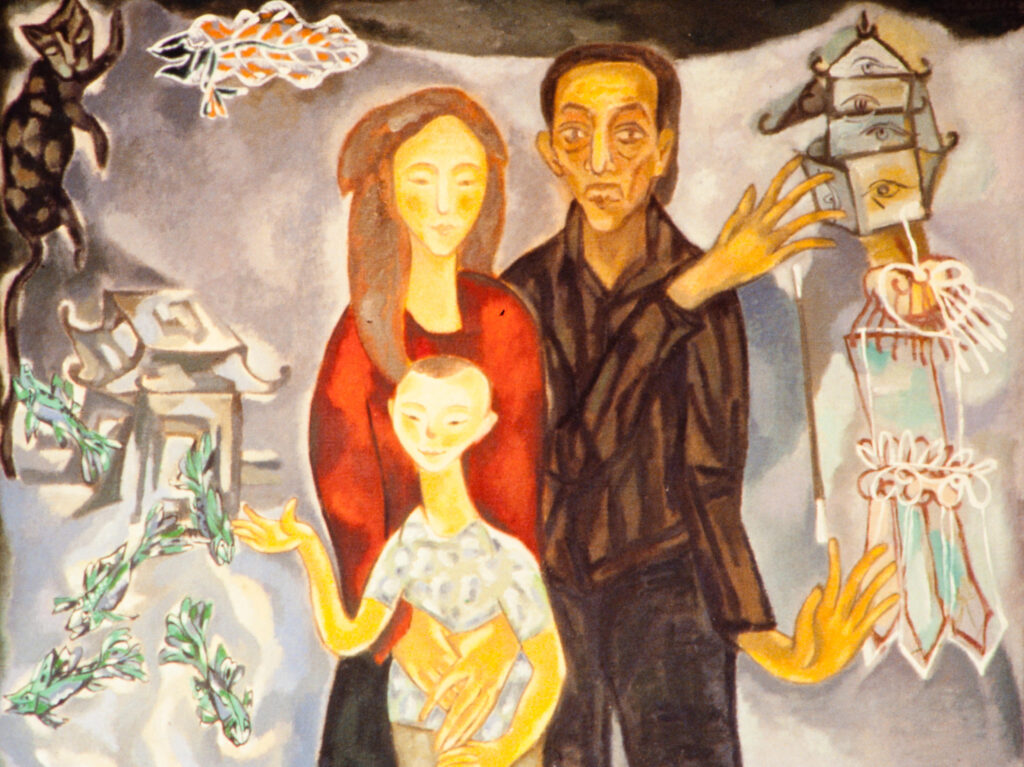

Australia resumed bilateral relations with Việt Nam in 1991 and the Queensland Art Gallery’s inaugural Triennial in 1993 was one of the first international exhibition projects to invite a Vietnamese artist to participate.2 Alison Carroll, Asialink’s Visual Arts Manager, was the first Triennial curator to travel to Việt Nam, visiting Hà Nội in August 1992. Following her recommendation, the curatorial committee invited Nguyễn Xuan Tiep to exhibit five poetic, semi-surrealist paintings, including The family 1991 and four paintings from his ‘Buffalo Boys’ series 1989–92. These paintings employ a fragmentary compositional style, incorporating elements from mythology, including people, animals and temples, and evoke memories of local spirituality and village life. Peter Mares, Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) correspondent and documentary filmmaker, said at the time: ‘The images have the suspended luminance of what he [the artist] describes as a Vietnamese “dreamtime”, a prehistoric past full of essential Vietnamese figures, animals and forces’.3

While they may not appear overtly radical to a contemporary audience, Nguyễn Xuan Tiep’s compositions and style would have been impossible only a few years earlier. As art historian Nora Taylor has indicated, abstraction and spirituality were forbidden, the inclusion of nudes was illegal until 1991, and references to spirits — particularly village spirits and deities — was taboo between 1945 and 1986 as ‘they competed with the Communist Party ideology promoted by the government’.4

Artist, writer and academic Nguyễn Quân was an important figure in APT1, contributing to the Triennial conference and the associated publication, Tradition and Change: Contemporary Art of Asia and the Pacific, though not exhibiting his work.5 Nguyễn Quân’s involvement was strategic, as he was both mentor and leader of a group of emerging artists that included Nguyễn Xuan Tiep. In Hà Nội, these artists would meet at the house of poet and translator Dương Tường, while several also worked for the state-sanctioned magazine Mӯ Thuât (Fine Art), of which Nguyễn Quân was editor-in-chief from 1986. Nguyễn Quân’s influential books Mỹ Thuật Của Người Việt (Art of the Viet) (1989) and Mỹ thuật Làng (Art in the Vietnamese Village) (1990) — co-authored with Phan Cẩm Thượng — theorised a way forward in the wake of Social Realism, and asserted that art could have a ‘national’ origin, yet not be a ‘state’ oriented product.6

Both Quân and Tiep emphasised the ‘time-honoured traditions’ of Việt Nam’s history as a ‘spiritual foundation and nutrient source’ in establishing and reviving a uniquely Vietnamese art.7 Tiep was regarded as ‘one of a small group of painters . . . forging a genuine and distinctive Vietnamese vision’, with Quân stating in an unedited version of his conference paper:

Among the young artists most successful [in Hà Nội] are those who are attached to national traditions, including those of ethnic minorities, with an introvert aesthetic attitude, attaching greater importance to the spiritual than to the outward . . .8

As Nora Taylor has commented, the return to village themes following de-collectivisation was also paralleled by an actual return to village craft production by families who had practised these art forms for generations. Thus, the village aesthetic employed by Tiep and others implicitly criticised a system of state control in favour of the time-honoured example of family-run artistic production.9

Tiep was the sole artist from Việt Nam selected to show his work in APT1, though Carroll recommended that an additional artist join the curatorial committee.10 Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) sponsored Nguyễn Quân’s travel to Brisbane, while Peter Mares sought sponsorship for Tiep to meet with other artists.11 This proved invaluable, as at the conclusion of the Triennial, a report submitted by the Queensland Art Gallery to DFAT and the Vietnam Ministry of Culture emphasised that ‘people to people contact’ was one of the most significant outcomes of the exhibition.12 The Gallery’s report cited Dương Tường — who had assisted with translation services for Tiep and Quân — and his statement published in the 24 October 1993 issue of Vietnam News: ‘The first Asia-Pacific Triennial constituted a remarkable event in the art life of the region’. Nguyễn Quân, while lamenting the difficulty of ‘representing a country by a single artist’, generously concluded:

It was the first time that Vietnam participated in an international exhibition in the Asia Pacific region. Of all its neighbours, Australia has become a country which, over the past two years, has had the most important co-operative relationships with Vietnam. This exchange has been crucial in our exposure to and assimilation with international cultural life.13

While the Triennial contributed to a positive relationship between Australia and Việt Nam, some promising developments were already in train. These relationships, as well as the synchronous opening-up of the two countries, created a sense of fellowship that was reflected in the next two iterations of the Triennial.

The Second Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT2, 1996): Mai Anh Dung, Vũ Dân Tân and Đặng Thị Khuê

For the second Triennial (APT2), the representation of Vietnamese artists expanded to three. They were selected by Australian curators Ian Howard and Dionissia Giakoumi, together with a team of Vietnamese experts — Nguyễn Lương Tiểu Bạch, Do Minh Tam, Ca Le Thang and Đào Minh Tri. At this time, Howard was the Provost of the Queensland College of Art (QCA), and had already initiated exchange exhibitions between Brisbane and Hà Nội in 1994.14 Howard highlighted the influence of decoration and pattern, folk and rural traditions, and storytelling and village life as significant in the work of all three chosen artists.15 While visiting Hà Nội in 1994 to organise the exchange exhibitions, Howard met the young art student Mai Nguyễn-Long. At Howard’s suggestion, Mai travelled to Brisbane to assist with translations in the lead-up to the exhibition opening, to act as an interpreter for visiting artists, and to study at QCA. Now an established artist in Australia with an intriguing and powerful art practice drawing on folklore, her work features in the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial (2024).

The three artists selected for APT2 continued the focus identified in the first Triennial of looking to the pre-Communist past as a source of inspiration. Mai Anh Dung exhibited two paintings referencing the ancient Cham culture and combining elements of installation with handcarved wooden frames. Vũ Dân Tân — who had founded Salon Natasha, Việt Nam’s first independent art space in Hà Nội, on his return from Russia — exhibited playful and innovative sculptures referencing street culture and vernacular art forms made from non-precious materials, including cigarette packaging.16 His Suitcases of a pilgrim 1996 was the first installation from Việt Nam to be shown in the Triennial. In the catalogue essay, his artist–partner Natalia Kraevskaia’s lighthearted description of his past and future lives (as a shoemaker and traveller) perfectly encapsulated the process of his art-making and the works he exhibited — miniature suitcases of wood and glass used for selling cigarettes on Hà Nội streets, and the ‘three-dimensional pieces, cut from cigarette packages, include mythical lion-dogs and phoenixes, smiling clowns, women angels and terrifying monsters’.17 With tongue-in-cheek humour, Kraevskaia described them as ‘gold, transparent and illusional, the kind of beings the artist believes to be real. The art works are toys, totems and icons at the same time’.18 Vũ Dân Tân visited Brisbane to install the works and they were displayed to intentionally evoke a corner shop or street stall.

The third artist featured in APT2 was Đặng Thị Khuê. Like her friends and colleagues Nguyễn Xuan Tiep and Nguyễn Quan, Đặng Thị Khuê had also begun to look towards folk art and village traditions for inspiration, with her images and motifs tapping into Việt Nam’s rich multicultural heritage and her own faith. Prior to the Đổi Mới era, she had found subtle ways to stretch the boundaries of what constituted state-sanctioned artwork. In addition, she had worked with Nguyễn Quân and Phan Cẩm Thượng on the magazine Mӯ Thuât (Fine Art), during the brief time they were able to publish the work of non-government approved artists.

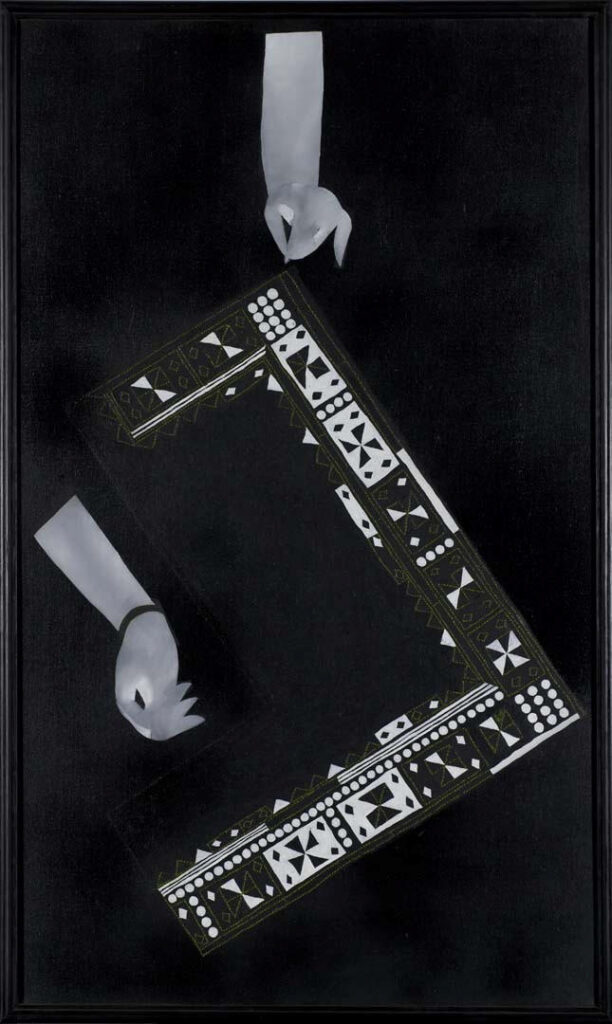

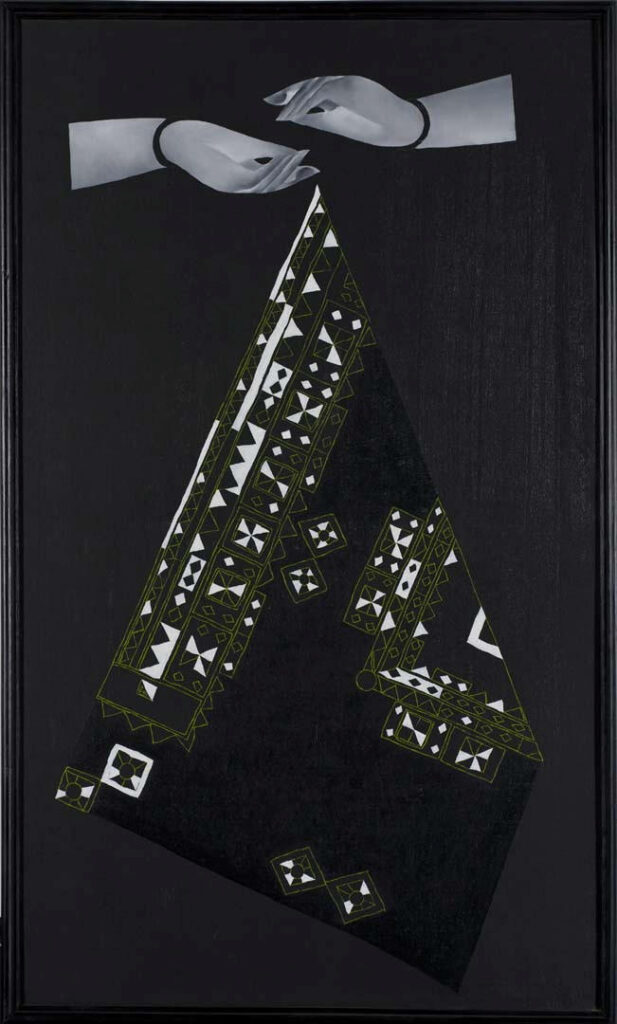

For her triptych comprising Light and a pair of hands, A pair of hands and stars and Space and a pair of hands 1995, Đặng Thị Khuê drew on folk art and textile traditions, as well as indigenous Đạo Mẫu mother goddess beliefs, while honouring the importance of women as providers, teachers and healers. The work features geometric designs characteristic of the textiles created by the indigenous communities in North Việt Nam, together with motifs of feminine hands holding poses typically associated with male deities. For Đặng Thị Khuê, referencing weaving practices and the matriarchal Đạo Mẫu figure of Princess Liễu Hạnh enabled her to gently assert the role of women and minorities. She was also prescient in recognising these indigenous textiles as valid art forms with complex languages of their own.

Đặng Thị Khuê, Việt Nam b.1946 / Light and a pair of hands (left) 1995; A pair of hands and stars (centre) 1995; Space and a pair of hands (right) 1995 / Oil on canvas / Three panels: 122.5 x 72cm (each) / Purchased 1996. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery │ Gallery of Modern Art

In his APT2 catalogue essay on Đặng Thị Khuê, Phan Cẩm Thượng stated: ‘She is endowed with an intense femaleness and her ideas are far more audacious than those of male artists’.19 With this comparison, he was arguably indicating that the artist’s references to women’s craft and women occupying positions of strength were challenging for the patriarchal status quo. Nora Taylor has also noted that female artists of the time, unlike their male colleagues who were also referencing village art forms, were less focused on a nationalist style and patriotic vision that would become distinctively ‘Vietnamese’ in the wake of Social Realism.

In her conference paper ‘Vietnamese Women Painters: Their Role, Characteristics and Artistic Creative Potential’, Đặng Thị Khuê asserted both that ‘humankind’s capabilities are not exclusively concentrated in long-established cultural centres, but that outside of these centres are time-honoured art traditions no less remarkable and distinct’, and that ‘inborn creative capacity and intellect are not the prerogative of the male half of humankind, but also lie deep in the artistic personality of women artists’.20

The years between the first and third Triennials proved fruitful for Australian–Vietnamese collaborations, ensuring that relationships remained active. Collaborative projects included the Salon Natasha partnership with Murwillumbah printers and the touring exhibition ‘Crosscurrents’; ‘Giao Luu Confluence: An Exhibition of Australian and Vietnamese Artists with Common Links’ at the Asialink Centre and Performance Space, Sydney; and ‘9 Lives’ at Casula Powerhouse, featuring Nguyễn Minh Thành, among others.21 By the late 1990s, Vietnamese artists had increased opportunities to exhibit at home and abroad, together with improved access to professional exchanges. Acknowledging these changes, both Nguyễn Xuan Tiep and Dương Tường described the art of this time as part of a ‘new artistic tradition’:

. . . indeed, it is this complex free generation that is setting the tone for the future of Vietnamese art. They do not content themselves with following up traditions. They are fashioning a new vision that keeps drawing substance from national roots and are accordingly creating a new tradition — the tradition of the New.22

The Third Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT3, 1999): Vu Thang, Nguyễn Minh Thành, Nguyễn Trung Tin, and My Le Thi (with Tim Johnson)

In the third Triennial (APT3), the relationships and dialogues established through the first two exhibitions were evident, with former participants and curators Nguyễn Xuan Tiep, Đặng Thị Khuê and Ian Howard contributing to the artist selection and the publication. Together with providing an essay on artist Nguyễn Minh Thành, Đặng Thị Khuê contributed an introductory essay ‘Contemporary Vietnamese art: A new stage’, while Nguyễn Xuan Tiep wrote on artist Vu Thang. Howard, who had selected artists for APT2, also wrote an essay ‘Scaling history and the long view, back home’. This conversational and peripatetic model of curatorship and collaboration has continued throughout the history of the Triennial.

Vu Thang’s pumiced lacquer work Promenade dans la nuit (Walk in the night) 1998 drew on the North Vietnamese indigenous histories of the H’Mong and Dao peoples, including the funeral houses in Tay Nguyễn architecture. A large, multi-part Chinese ink and paper work by Nguyễn Minh Thành titled Portrait of mother 1998 incorporated two flanking works of comparable size that referenced women and rural life. In a fascinating apposition, Nguyễn Minh Thành posited the design and decoration of pagodas and temples in Việt Nam as a vernacular equivalent to contemporary art installation. Nguyễn Trung Tin’s nostalgic look at the disappearance of once-ubiquitous local customs was captured in two large paintings Streets memorial and Memories of the alley, both 1998–99.

A collaboration with Australian painter Tim Johnson meant that My Le Thi became the first Australian-based, diasporic Vietnamese artist represented in a Triennial.23 The next would be Melbourne-based Phuong Ngo with their ‘Collaborative racist paintings’ 2020–ongoing in APT10. In the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial, Mai Nguyễn-Long will be the third Australian–Vietnamese artist to exhibit in the Triennial.24

APT2002 and The 5th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT5, 2006): Đinh Q Lê and Tuan Andrew Nguyễn

APT2002, the fourth iteration of the Triennial, had no Vietnamese representation, as the exhibition narrowed its focus to a smaller group of artists to allow for more comprehensive individual surveys; however, the fifth Triennial (APT5) — which was delayed a year to coincide with the opening of the new Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA) building — returned to its typical multi-artist format, and to its inclusion of Vietnamese artists.

With the opening of the Gallery’s second building, the representation from Việt Nam grew. A central artist for APT5, Đinh Q Lê — one of the first artists to relocate from the United States to Hồ Chí Minh City in 1996 — contributed three large-scale projects that amply filled GOMA’s generous new gallery spaces. The three-channel video installation The farmers and the helicopters 2006 provided a complex counter-narrative to the mythologies of the Việt Nam–American War (1959–75), and was shown with the sculptural installation Lotusland 1999, together with the related Damaged gene 1998, both of which highlighted the ongoing devastation wrought by the defoliant Agent Orange, used by the US military during the war. Đinh’s intention was to exhibit the actual helicopter featured in The farmers and the helicopters, and though this proved impracticable, he was able to bring the young farmer who had built the aircraft to the Triennial’s opening weekend.

Tuan Andrew Nguyễn developed a group of paintings entitled Proposal for a Vietnamese Landscape 2006 for APT5, on which he collaborated with graffiti artists, landscape painters and graphic designers across three generations to capture the conflicted visual terrain of Việt Nam’s contemporary cities. Both Đinh Q Lê and Tuan Andrew Nguyễn were key figures in the art scene in Hồ Chí Minh City after 1995, at which time returned diasporic artists (known as Việt Kiều) and foreign and local artist communities co-existed. Đinh Q Lê’s Sàn Art, founded in 2007, was one of Hồ Chí Minh City’s few spaces that promoted supportive relationships between artist friends and colleagues, and artists Tiffany Chung, Hà Thúc Phu Nam and Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn were amongst its advocates.25

APT5 signalled a shift in the presentation of artwork from Việt Nam. In part, this reflected a change in the Vietnamese art scene, but also in curatorial methodology. Electing to work with artists who had already established international careers meant that the fifth iteration of the Triennial could present ambitious large-scale works, often exploring universal subjects, such as international relations, migration, technology and war. This stood in contrast to the first three Triennials, in which artworks from Việt Nam were generally modest in both scale and materials. These earlier works were also concerned with a specifically Vietnamese style and language as a way of addressing various controls on artistic expression, firstly under French colonial rule and then the adherence to state-sanctioned Social Realism.

The 6th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT6, 2009): Mekong Project, Bùi Công Khánh and Jun Nguyễn-Hatsushiba

For the sixth Triennial (APT6), the Mekong Project — co-curated by former QAGOMA curator Russell Storer with artist and researcher Richard Streitmatter-Tran — shifted attention to the Greater Mekong subregion, expanding the curatorial perspective on Việt Nam by acknowledging pre-modern formative histories and geographical relationships.26 The Mekong Project highlighted shared histories, and presented a multilayered view of a region undergoing rapid transformation. It contrasted the changes brought about by a rise in international trade and investment, including increased mobility of people, information and ideas via new highways and communication networks, alongside Buddhist values and longstanding traditions that were under extreme pressure from external influences. It also marked the first representation of neighbouring regions Laos and Cambodia in the Triennial. Jun Nguyễn-Hatsushiba’s video work The ground, the root, and the air 2007 was filmed along the Mekong River in Laos, and, like a group of early ceramic blue-and-white vases by Bùi Công Khánh, contrasted tradition with the realities of contemporary life. The curators remarked that ‘looking back in order to move forward seems to be one element common to each of the works’, and this principle was evident in the artists’ references to traditional materials, historical figures and events.

The 7th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT7, 2012): Nguyễn Manh Hung, Nguyễn Minh Phuoc, Nguyễn Thái Tuấn, An-My Lê, Tiffany Chung and the Propellor Group

The seventh Triennial (APT7) featured the largest representation of Vietnamese artists to date across a range of media. A three-metre-high tower installation by Nguyễn Manh Hung titled Living together in paradise 2009 referenced Hà Nội’s Soviet-era architecture, suggesting the uneasy coexistence of past and present. For Nguyễn Manh Hung, these buildings were ‘vertical villages’, with people occupying them as they would modest dwellings in a rural environment. Having grown up in one of these towers, the artist likened his experience to that of village life, where everyone knew each other, gardens took over every corner, and public space was occupied for private living. As the title suggests, the work addressed the adaptive ways in which Vietnamese people inhabit their cities, rather than the architecture itself.

Nguyễn Minh Phuoc’s video Red étude (Khuc Luyen Do) 2009 also drew attention to the contradictions between past and present, combining small, personal moments with overtly political gestures, while Nguyễn Thái Tuấn’s semi-surrealist series of ‘Black paintings’ 2008–09 depicted a cast of figures in locations redolent with multiple histories, evoking the omnipresence of official state accounts and the permeability of memory.

Nguyễn Manh Hung, Việt Nam b.1976 / Living together in paradise (installation view and detail) 2009 / Mixed media installation / Installed dimensions variable / Courtesy: The artist and Art Vietnam Gallery, Hanoi / Photographs: M Sherwood, QAGOMA

Nguyễn Minh Phuoc, Việt Nam b.1973 / Red étude (Khuc Luyen Do) (stills) 2009 / Digital video on DVD: 5:00 minutes, colour, sound; compressed Quick Time file on hard drive and Mini DV, ed. 2/5 / Purchased 2011. Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Grant / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery │ Gallery of Modern Art

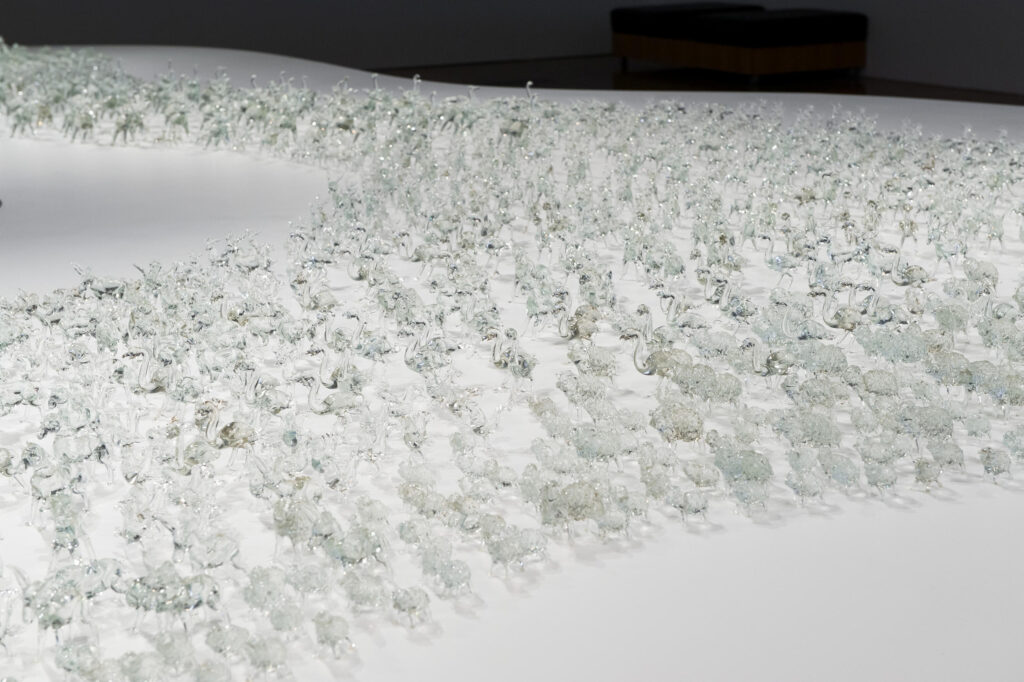

For the first time since Đặng Thị Khuê exhibited her work in APT2, two female artists from the Vietnamese diaspora (both raised in the United States) were included in APT7. An-My Lê’s cinematic photographs from her ‘Events Ashore’ series 2010 focused on quotidian pre- and post-combat routines that she viewed while she was embedded as a photographer with the US Armed Forces, with the works carefully recalibrating the aesthetic tropes of miliary combat and the theatre of war. Tiffany Chung, a foundational member of San Art in Hồ Chí Minh City, contributed an epic installation of 4000 tiny glass animals, which were commissioned from a glass craftsman working in Việt Nam. In roaming with the dawn – snow drifts, rain falls, desert wind blows 2012, the artist carefully arranged the fragile animals on an organic-shaped plinth, their numbers swelling outwards in a volume suggestive of a migratory hoard. Chung’s work drew on her empathy with those with experiences of forced migration and displacement, as well as her fear of environmental catastrophe. Lastly, the Propellor Group’s collaborative mural Birds of No Nation 2012 was part of their project called Viet Nam The World Tour (VNTWT), in which they conceived of a ‘rebrand’ of Việt Nam and other nations whose international reputations had been forged through colonialism, war and tourism.

Tiffany Chung, Việt Nam b.1969 / roaming with the dawn – snow drifts, rain falls, desert wind blows (the artist installing her work, and detail) 2012 / 4000 hand-blown glass animals, wooden plinth / 50 x 1000 x 700cm (approx., installed) / Commissioned 2012. Queensland Art Gallery / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery │ Gallery of Modern Art / Photographs: M Sherwood, QAGOMA

The 8th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT8, 2015): UuDam Tran Nguyễn

Perhaps to balance the large representation in APT7, UuDam Tran Nguyễn was the sole Vietnamese artist in the eighth Triennial (APT8). Having returned to Hồ Chí Minh City after a period living overseas, he was struck by the changed character of the streets and the number of people riding motorcycles. His multichannel video work Waltz of the machine equestrian 2012 involved choreographing these ubiquitous motorcycle riders wearing brightly coloured rain-capes into an artistic ritual inspired by common routines seen on city streets.

The 9th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT9, 2018): Nguyễn Trinh Thi and Ly Hoàng Ly

The ninth Triennial (APT9) offered an opportunity to work with two Vietnamese artists who introduced a feminist perspective to the exhibition. Independent filmmaker and moving-image artist Nguyễn Trinh Thi’s subtle and brilliant installations juxtaposed non-fiction with popular movies, found photographs and her own recorded footage. Acknowledging the artist’s position of power behind the lens, Nguyễn’s practice addresses overlooked or misinterpreted histories. She focuses on the individuals from the Đạo Mẫu and Cham communities, as well as those oppressed by structures of power and patriarchy, including women, minorities and the colonised. In APT9, she premiered Fifth Cinema 2018, an important theorisation of an indigenous cinema combining her own moving images with found footage. Nguyễn explained the impetus for her works as empowerment:

I just want to give agency to the suppressed voices. So I think the most important gesture in this work is that of giving a woman a chance to speak.27

Ly Hoàng Ly presented a group of works in various media that addressed experiences of motherhood, domestic life, immigration and displacement. An artist ‘book’, boat home boat 2016 — part of her series of works titled 0395A.ĐC 2011–ongoing — took on the sculptural form of a concertinaed book, and was shown alongside Ashes 2013, a poetic collection of sculptures and paintings reflecting on essence, which used cow bones from Phð soup as a point of departure.

The 10th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art (APT10, 2021): Nguyễn Thị Châu Giang, Phi Phi Oanh and Nguyên Phuong Linh

The tenth Triennial (APT10) again focused attention on female artists from Việt Nam, with works by three artists born in the 1970s and 1980s featured. Nguyễn Thị Châu Giang, Phi Phi Oanh and Nguyên Phuong Linh all engage with traditional art forms or foundational myths that are bound up with national identity. Unfortunately, with the COVID-19 pandemic still closing international borders in 2021, the artists were not able to travel to Australia to install their work or attend the opening.

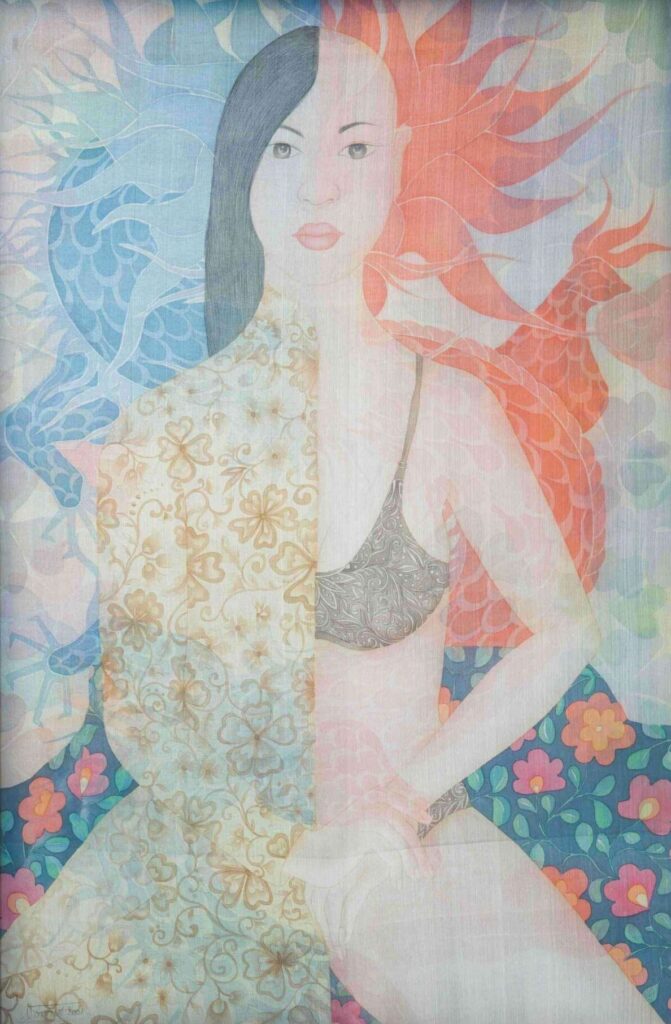

Nguyễn Thị Châu Giang’s vibrant group of suspended silk paintings of women — Inside of Us 4 2020 and Our Time 2021 — addressed the parallel legacies of figurative silk painting and the characterisation of women in Việt Nam. She subtly undermined the female archetypes perpetuated in silk painting, presenting each of her subjects as resolutely real, through the inclusion of contemporary accoutrements and the motif of the dragon as a symbol of internal contradictions between public and private lives, and strength and vulnerability.

Installation view (and detail) of Nguyễn Thị Châu Giang’s double-sided ink and watercolour on silk paintings Inside of Us 4 2020 and Our Time 2021 in APT10, Gallery of Modern Art, 2021 / Courtesy: The artist / Photographs: M Campbell, QAGOMA

Phi Phi Oanh’s sublime Fissio 2020–21 explored the technical and conceptual qualities of lacquer as a contemporary medium. A temple-like installation of 12 carved and lacquered wooden boards, it was inspired by the once-ubiquitous lacquer plaques inscribed with ideogrammatic couplets (hoành phi câu đối) framing shrines and altars. Oanh connects the disappearance of the custom with the contemporary dispersal of people and families from their local histories typically grounded in place, especially ancestral towns. Her work foregrounds lacquer’s relationship to national cultural narratives, and the role of language and place in the constitution of collective identity.

Phi Phi Oanh, United States b.1979 / Fissio (installation views) 2020–21 / Lacquer on wood / 12 parts: 215 x 50 x 15cm (approx., each) / Purchased 2021 with funds from Tim Fairfax AC through the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art Foundation / Collection: Queensland Art Gallery │ Gallery of Modern Art / Photographs: N Harth, QAGOMA

Nguyễn Phuong Linh’s surreal, minimalist installation, The encounter 2021 combined enigmatic sculptures and videos in a space echoing the gendered structure of a Vietnamese household. The disparate, yet relational, elements reflected on ‘memory, heritage and the changing landscape of Vietnam’, particularly Nam Định province in North Việt Nam.28 Phuong Linh chose to contrast materials like PVC, bright LED lights and paint with the materials used in the region’s traditional crafts, such as carved wood, and copper and cassiterite (tin dioxide) casting. The space was dominated by a screen showing the absurdist disembodied head of the mythical princess Liễu Hạnh, suspended over a luxury swimming pool, with the work indicating a return to the theme of Đạo Mẫu, the mother goddess religion, as a significant aspect of Vietnamese culture and an enduring source of inspiration for contemporary art.

This brief overview reveals the importance of ongoing relationships to the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art retaining its relevance and building on its strengths for future iterations; however, the underrepresentation of women needs to be addressed. Of the more than 25 artists from Việt Nam, or its diasporas, represented in ten Triennials, only eight have been women. Between the first and sixth iterations of the exhibition, only one female artist from Việt Nam was represented, and of the seven Vietnamese artists in APT7, only two were women. In addition, artists from the Australia–Việt Nam diaspora have not had substantial representation, with only three artists featured in all ten Triennials.

While only providing a glimpse of Việt Nam’s diversity of artistic production, various thematic threads can be discerned throughout the Triennials — the use of local materials; references to vernacular beliefs and folk art; responses to the trauma of displacement; the precariousness of freedom of speech; the invisibility of women and minorities; and reflections on the human cost of globalisation, alongside the rapid growth of urban environments and the exploitation and devastation of the natural world.

In the lead-up to the 11th Asia Pacific Triennial, it is apparent that many of these threads appear in the works of the latest group of Vietnamese artists selected for inclusion — the site-specific installation Khu Vườn Lạc Hướng (A disoriented garden) 2023–24 by Trương Công Tùng; Lê Giang’s gem paintings that critique ideals of the landscape in Vietnamese culture; Lê Thuý’s ambitious architectural installation of silk and lacquer; and a large group of ceramic and carved wood works by senior figure Bùi Công Khánh, whose earlier porcelain vases featured in the Mekong Project in APT6. Lastly, the inclusion of Mai Nguyễn-Long (who acted as Đặng Thị Khuê’s interpreter in APT2) — with The Vomit Girl Project 2024, referencing folk histories and diasporic identities — brings past stories and relationships of the Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art and their continuing relevance into the present.

Mai Nguyễn-Long, Australia/Việt Nam b.1970 / The Vomit Girl Project (detail) 2024 / Glazed and unglazed clay / Installed dimensions variable / Courtesy: The artist and Michael Reid, Sydney and Berlin / Photograph: Bernie Fischer

This paper expands on the research presented in the author’s original article ‘Vietnam in the Asia Pacific Triennial’, first published in the TAASA Review, the quarterly journal of The Asian Arts Society of Australia (TAASA), vol.32, no.4, December 2023.