https://www.womenandperformance.org/ampersand/29-1/nguyen

Abstract

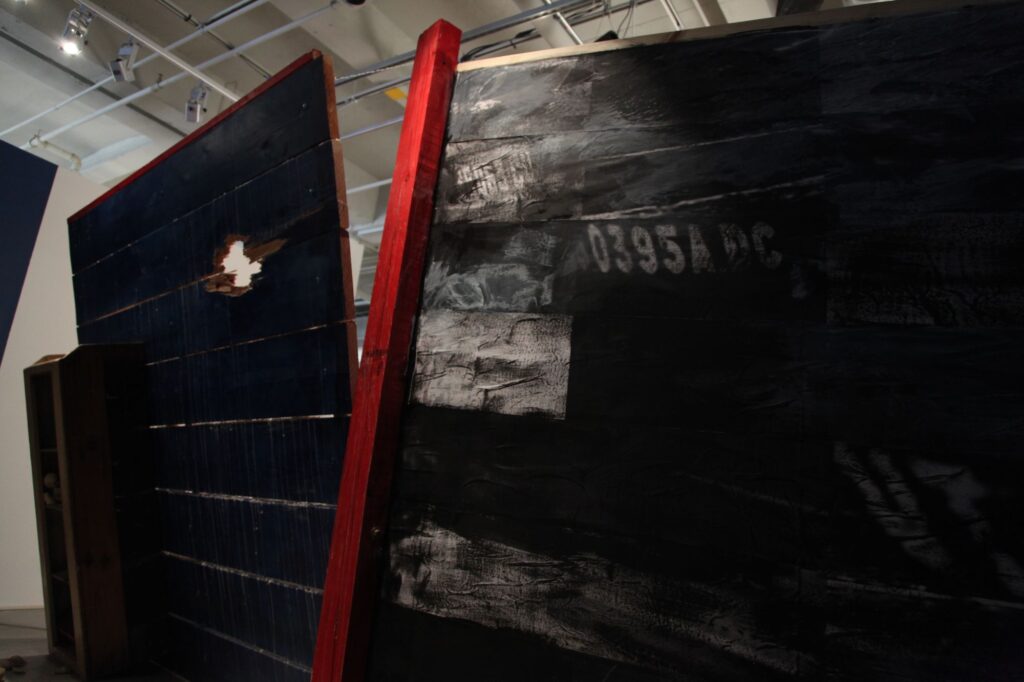

The end of the Vietnam/American War lead to one of the largest exoduses of the latter part of the twentieth century: more than 3 million people escaped from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos over the course of two decades starting in 1975, many by boat and an estimated 1 million died at sea. How do you witness and retell stories of violence in the aftermath of war and dispossession at sea in the context of U.S. empire and Vietnamese socialist revolution? Project 0395A.ĐC, a multi-media installation by Vietnamese artist, Ly Hoang Ly, intentionally structures and choreographs disorientation to grapple with the condition of being dispossessed at sea, as the Vietnamese refugee is suspended at sea and entangled in histories of French colonialism and caught at the crux of U.S. imperial war and Vietnamese socialist revolution. I argue that disorientation is a performative experience and method that performs an act of refusal to break voyeuristic modes of consuming histories of violence and reorients the body to another theory of Vietnamese refugee subjectivity. I analyze how Ly creates a performative installation and performs with water as the core aesthetic material used to frame, dialogue, and re-narrate a story of Vietnamese refugee subjectivity.

How do you witness and retell stories of violence in the aftermath of war and dispossession at sea colliding at the crux of U.S. empire and Vietnamese socialist revolution?

The Gulf of Thailand

The pirate ship rammed to break our boat.

Then the pirates jumped on to our boat.

They carried machetes, hammers

And other weapons to rob us right there.

At that moment our boat began to sink.

The pirates forced all my people to board their ship.

They forced … then body searched everyone.

[…]

then they threw us back in our boat.

We didn’t know where to go now.

The boat was filling with ocean water

– excerpt from Kiệt Trương’s oral history, home | boat, transcribed by Ly Hoàng Ly

The end of the Vietnam/American War lead to one of the largest exoduses of the latter part of the twentieth century: more than three million people escaped from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos over the course of two decades starting in 1975. Many fled by boat and an estimated one million died at sea (UNHCR 2000, 79). During the postwar period, Vietnam faced extreme poverty, large-scale unemployment, limited food supply, and rampant corruption. In addition, one to two million military and civilian personnel who were associated with the former Republic of Vietnam and the United States were prosecuted as war criminals and imprisoned in re-education camps. An estimated 400,000 to one million people were forcibly relocated to “new economic zones” (UNHCR 2000, 82).

The opening excerpt is a quote from Kiệt Trương, a Vietnamese boat refugee whose oral history was recorded for Project 0395A.ĐC, a multi-media installation by Ly Hoang Ly. Trương’s narrative captures the dangers of escape at sea for millions of Vietnamese refugees after the Vietnam/American War: a constant threat of drowning, pirate attacks, typhoons, capsizing, running out of food and drinking water, and being lost at sea. Trương’s escape takes place after he and his family escape for a second time off the coast of Hà Tiên Bay in southern Vietnam. His family makes it to the Gulf of Thailand and is met with Thai pirates. Pirate attacks were flagged by Vietnamese refugees and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) as one of the greatest potential dangers of escape by sea. According a UNHCR report in 1981, “349 boats had been attacked an average of three times each; 578 women had been raped; 228 women had been abducted; and 881 people were dead or missing” (UNHCR 2000, 87). These statistics are based on reports from refugees who made it to refugee camps, still, countless numbers of attacks and deaths are unreported for the people and boats that did not make it to shore or landed elsewhere. Surrounded by impending death through pirate attacks, a cracked boat, and the overpowering seepage of water, Trương’s story reveals the precarity of escape at sea, the overwhelming death-world refugees face in the unknown of the water.

Project 0395A.ĐC was exhibited at the School of the Art Institute Master of Fine Arts Show in Chicago, Illinois on May 2013. Project 0395A.ĐC takes its name from a photograph Ly found online while searching for pictures of Vietnamese refugees during the boat exodus as part of her research for the art installation. Series of numbers and letters marked the endless cargo ships and fishermen boats that carried Vietnamese boat refugees. The randomness of the series of numbers and letters represents the arbitrariness of those who were able to escape, of the probability of life and death at sea, of assigned numbers to refugees who made it to shore and were identified through U.N. paperwork as “rescued” subjects, of the boats and people who did survive the crossing.

“Disorienting,” “unorganized,” “difficult to walk through,” and “dizzying” are some of the critiques of Project 0395A.ĐC according to Ly. Disorient is defined as to “make (someone) lose their sense of direction” and “make (someone) feel confused.” While other definitions of disorient, according to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, mean “to cause to lose bearings: displace from normal position or relationship” and “to cause to lose the sense of time, place, or identity.” Project 0395A.ĐC intentionally structures and choreographs disorientation to grapple with the condition of being dispossessed at sea, as the Vietnamese refugee is suspended at sea and entangled in histories of French colonialism and caught at the crux of U.S. imperial war and Vietnamese socialist revolution. I argue that disorientation is a performative experience and method that carries out an act of refusal to break voyeuristic modes of consuming histories of violence and that reorients the body to theorize Vietnamese refugee subjectivity differently. A Vietnamese refugee subjectivity that is not dependent on a desire for wholeness but offers a space to exist within the fragments and entanglements of the aftermath of colonialism, imperialism, and socialist revolution.

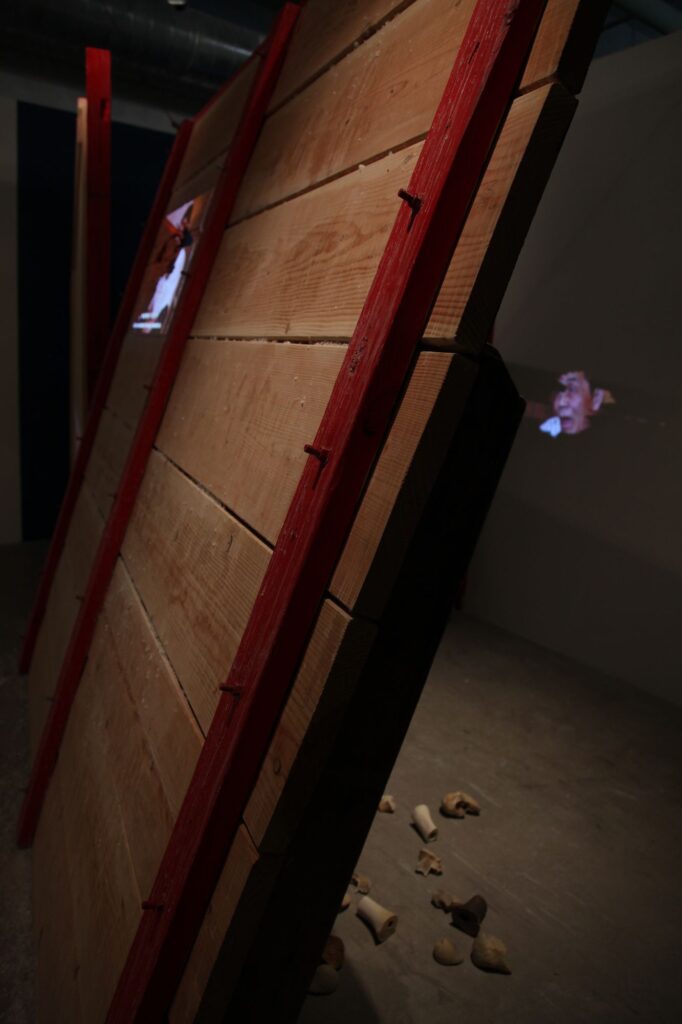

Makeshift architecture is a historical practice of constant spatial configuration and reconfiguration, which embeds within it a sense of impermanence due to colonial and imperial dispossession. Ly plays with the practice of makeshift architecture to create an installation that configures found objects as physical conditions of disorientation in Project 0395A.ĐC. To do so Ly’s makeshift choreographs how the body moves through the installation to disrupt direct access to Trương’s oral history and offer fragmentation as a process of Vietnamese refugee ontology and epistemology. The concept of makeshift was developed in a conversation with Vietnam-based performance and visual artist, Tuấn Andrew Nguyễn, about the temporary construction of home spaces in Vietnam in the context of French colonization and U.S. military intervention wherein Vietnamese subjects are ready to move at any moment due to poverty, war, and forced removal by military and/or government forces. The resulting process is a makeshift structure built through a gathering of available building material that can be portable, discarded, or relatively easy to construct and disassemble to build temporary refuge.

What do you carry with you when you escape from home? What would you take with you on your journey to freedom? Vietnamese refugee history is embedded in everyday objects both present and absent. During and after the Vietnam/American War visual evidence in the form of material belongings such as photographs, military accouterments, and official documents revealing affiliation or connection to the Republic of Vietnam government and the U.S. were burned, shredded, torn, and/or buried, and sometimes burned and then buried to protect individuals and families. The process of eviscerating all evidence of a former life protected one’s self and family under a new regime. The evidence could be used to persecute people into re-education camps, which could lead to execution and/or hard labor resulting in a slow death. The absence of objects reveals just as much as their presence in what could be salvaged or taken in the journey on the boat. Everyday objects that could be carried uncover other fragments of what people thought was needed for survival and memory of home. “I carried only the clothes on my back,” are the words that echo from so many Vietnamese refugees who escaped in the middle of the night when their boat was rushed and unexpectedly left before or after schedule, all dependent on the weather at sea and the political climate on land. Sometimes people were able to quickly grab their identification documents, gold, a photograph, and/or farming tools. It is in the everyday that the archives of war, forced migration, home, nation, and identity emerge and, in its erasure, that histories of state violence are revealed.

choreographing disorientation

Ly plays with choreographing the body’s relationship to witnessing and with sight and sound to trouble the very ethics of witnessing and subject formation. There is a tight opening on the right side of the installation. It is about 6 feet high and 3 feet wide at the base. At this point, the audience can choose whether to enter the opening or not. The cue for some is seeing other people enter. The only clue for what may lie inside the installation could lie in the audience’s curiosity to whether the projection of Trương’s face was inside the installation. Once the audience enters inside the opening, they must duck their heads, contract their bodies towards their torsos while hunching their backs, and slowly step inside the body of the boat/installation. The audience’s movement can disrupt and shift the formation of the installation at any moment. As the audience enters they must walk around or over a ripped beige hammock and are met with a scattering of ox tail bones.

As the audience moves further inside the hold of the boat/installation, Trương’s face is projected on the wall with a set of headphones next to his image where the audience can hear the audio from his interview with Ly. Dispersed throughout the installation are Trương’s body, face, Vietnamese voice, and English translation text of his interview with the overwhelming sounds of waves crashing against the shore of Lake Michigan playing overhead. The audience cannot easily locate Trương’s story; they must navigate fragments of Trương body and voice through the objects scattered in the installation and disconnected video, audio, and languages of his interview (English as translated text on the projection and Vietnamese in the sound recording). Project 0395A.ĐC meditates on subject formation through cultural production, playing with narrative visually and sonically as the makeshift structure choreographs the audience’s corporeal relationship to the story and the subject-troubling visibility to disorient the audience and perform another mode of theorizing subjectivity.

Stillness

Stillness is performed not as a performative opposition to disorientation and chaos, but as a meditative performance that opens up an embodied experience of deep listening.

Located on the lower right side of the left wooden panel is Ly’s performance art video entitled, “I make myself a rock to experience geopolitical issues.” Ly is wearing a dark red velvet áo dài, a traditional Vietnamese dress. She lays in a fetal position on the banks of Lake Michigan, the closest body of water to Trương, who is resettled in Chicago. The video plays on a loop as waters of Lake Michigan crash onto her body and seep through her dress and onto her flesh. Ly continues to lay there in silence. The audio surrounding and framing the exhibition is taken from this video.

Women have been figured as a symbol of the nation, during the war as warrior, farmer, and mother and after the war as the symbol of the country’s futurity due to her ability to reproduce and give birth to and cultivate a new independent nation (Bergman 1974; Das 2007). In “I make myself a rock to experience geopolitical issues,” Ly uses her body to bear witness to what the water is telling her. Red symbolizes both luck and communism in Vietnam. The red áo dài marks both these meanings donned on Ly, marking her body as a gendered and racialized subject of the nation and war. As a Vietnamese woman born in 1975, the same year the Vietnam/American War ended, Ly’s positionality in relationship to the diaspora and postwar subjectivity is important. I mention Ly’s relationship to the war to think through what it means to create this piece, and what it means to witness from the other side of war. How does this work reveal what cannot be fully captured–the failures, ellipses, refusal, and imagination–in an effort to piece together a painful and divisive archive? Ly’s position in relationship to the work is about the act of witnessing and the burden of memory. What does it mean to witness a story from the other side of war, what can you know and what can you never know?

It begins with stillness.

Ly as a Vietnamese woman, born in Vietnam right after the war, performs as both a figure of Vietnam as a nation and social actor intervening on the divide between the opposing sides of the Vietnam/American War through stillness and a meditation with water. Here the water is the archive that Ly bears witness to, feeling the thrashing of water against her body, feeling the heaviness of the water as it collects onto the velvet fabric of her dress, and allowing it to soak into her skin until she feels its coldness in her bones. “I make myself a rock to experience geopolitical issues,” reflects on the positionality of the artist through the gendered labor of memory and nationhood. Her body marks her as both native because she is born in Vietnam but also as other in the Vietnamese diaspora. It is through stillness with the water that Ly pays deep attention to the water that is inside her, the inherited trauma of colonialism war, and socialist nation building. She listens with her body to the water, to the waves that crash against her collecting water on her velvet dress, seeping through her flesh, and sinking into her bones.

She listens.